VIRGILIO BARCO

Malcolm Deas, LAC’s Emeritus Fellow, offers a brief portrait of former Colombian President Virgilio Barco, the subject of his latest book

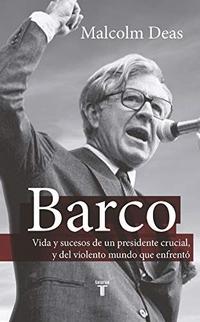

Last September I published Barco. Vida y sucesos de un presidente crucial, y del violento mundo que enfrentó (Bogotá: Taurus, 2019). This was the subject of my talk at the LAC History Seminar on 13th February.

Though the book is not a conventional biography, I began the talk with a defence of political biography, a genre not much favoured in Latin America, and some remarks about the deficiencies of much political science, which has little to say about leadership or distinct political conjunctures. Personalities matter: who can understand Argentine politics without some knowledge of Perón? Biographies also teach complexity, and lead one to question stereotypes: they surprise and can lead one to reject many received ideas. They are not much favoured by the French, whose Annales school of history is also of only marginal usefulness when it comes to politics.

I began with Barco’s ancestry and youth. In a country where political allegiance is often assumed to be hereditary, Virgilio Barco had prominent forbears in both Colombia’s traditional parties, Liberal and Conservative. On his father’s side, his grandfather General Virgilio Barco was Conservative, a participant in at least three civil wars. On his mother’s, he descended from General Justo L. Durán, one of the most prominent Liberal commanders of the Guerra de Los Mil Días, assassinated in 1922. Barco later said that it was this assassination, witnessed by his grandmother, that made him choose to be a Liberal. Both were leading figures in the politics of what became the Department of Norte de Santander, the scene of Barco’s first steps in politics, and a region that always had a high place in his loyalties: Barco never thought like a born Bogotano.

I had access to his personal archive. It contains a correspondence of some 160 letters between the young Virgilio and his father Jorge, a lifelong but un-sectarian Conservative, while he was a student at MIT in the late nineteen-thirties and early forties. One sees the influence on him of the USA of the New Deal, of FDR, and of World War II, which he and his father follow closely and frequently comment on. They also both write about Colombian politics. Barco received a superb engineer’s education at MIT. He always remained something of an engineer, and with subsequent spells of study in Boston University and MIT and appointments to Washington was perhaps of all recent presidents of his country the one who best knew the United States. There are many areas of life and culture that conventional studies of US-Latin American relations inexplicably leave out.

Barco’s father left a substantial fortune, having started at the age of 16 as the agent for Singer sewing machines in Barranquilla. He also inherited royalties from the petroleum Concesión Barco, obtained by his grandfather in 1905. These gave him financial independence, though not the vast riches of the fantasies of some on the Colombian left – and right. Autonomy is a constant feature of Barco’s politics, in his ministries, in his Bogotá alcaldía and his presidency: he nominated his own teams, independent of ex-presidents and party bosses, and formulated his own policies. Wealth reinforced his natural independence of character. He lived well but with no excessive lujo, and was not personally interested in business. He scrupulously avoided conflicts of interest throughout his career.

My biographical essays do not pretend to give a complete account of his career and his presidency – for the last I recommend the book I edited with the late Carlos Ossa, El Gobierno Barco, Política, Economía y Desarrollo Social, Bogotá, Fedesarrollo and Fondo Cultural Cafetero, 1994. After the chapter on his ancestry and youth, I explore with the aid of his correspondence and other particularly valuable local sources the provincial politics of Norte de Santander in the late 1940s, the era of the so-called violencia clásica. The other two major chapters in the book cover his time as alcalde of Bogotá and President of the republic. The first shows his exceptional capacity and success in what is perhaps the second most important executive office in the country and tries to suggest the many ways in which urbanization changes politics, being a major factor in the decline of sectarian loyalties. My discussion of his presidency attempts to show both the inherent weakness of the national government when faced with multiple threats to public order in diverse regions of the country, and the importance of Barco’s refusal to contemplate any deal with the drug cartels, then at their most menacing. As often, all this was too much to cover in a single one-hour lecture. I hope I succeeded in awakening interest, questioning some received versions and even in exciting admiration – a feeling perhaps too rare among academics – for a remarkable statesman.

Malcolm Deas, 1st April 2020